Bread, the staff of life. All sorrows are less with bread. We pray for our daily bread. Bread has been instrumental in sustaining the diets and wages of rural peasants and the urban poor throughout history. Large swathes of the world’s population depend on bread for sustenance which made the bread supply a concern of government and rulers alike. In Pharaonic Egypt, government workers were paid in bread and grain. Rome built its empire on a network of bakeries as the average citizen ate two pounds of bread daily. Even as society shifted to a meat-centered diet in the Middle Ages of Europe, bread anchored the meal. It was one of the cheapest forms of energy as meat and vegetables were sparse. In contemporary society where fruits, vegetables, and meat are now plentiful, bread has become less central to our physical survival even as its pricing remains central to our happiness.

Bread is life.

Those who can afford to dine out believe that bread should be served gratis. Diners will even complain on social media and rally against restaurants that have the audacity to charge for their bread baskets. Still, rising food and labor costs have prompted restaurateurs to charge for bread. However, even as contemporary food movements celebrate landrace grains and heirloom vegetables, bread has remained relatively cheap and devolved into a dismal state where anything that contains flour passes for bread. Spongy potato rolls. Floppy pitas. Fluffy sourdough loaves. Pasty sandwich loaves. Whether the dough was mixed by hand or slapped together in an industrial mixer, it can still be labeled as ‘bread’. Whether it contains only flour, water, salt and yeast, or a slurry of flour, water, flavorings, yeast, conditioners and enzymes, it can still be labeled as ‘bread’.

Naturally, the dichotomy of cost and quality has created factions within the baking industry: large-scale baking conglomerates versus small-scale, artisan bakers. Artisan bakers treat baking as a synergistic process in which they manipulate time and temperature to the yeast as it ferments the flour. Industrial bakers treat baking as a reductive process in which ingredients and techniques are isolated and recombined to create breads with specific characteristics. Where artisan bakers are concerned with coaxing flavor from the grain, industrial bakers are concerned with exerting control over the baking process to produce a finished loaf in the desired timeframe so the bread can be sold cheaply.

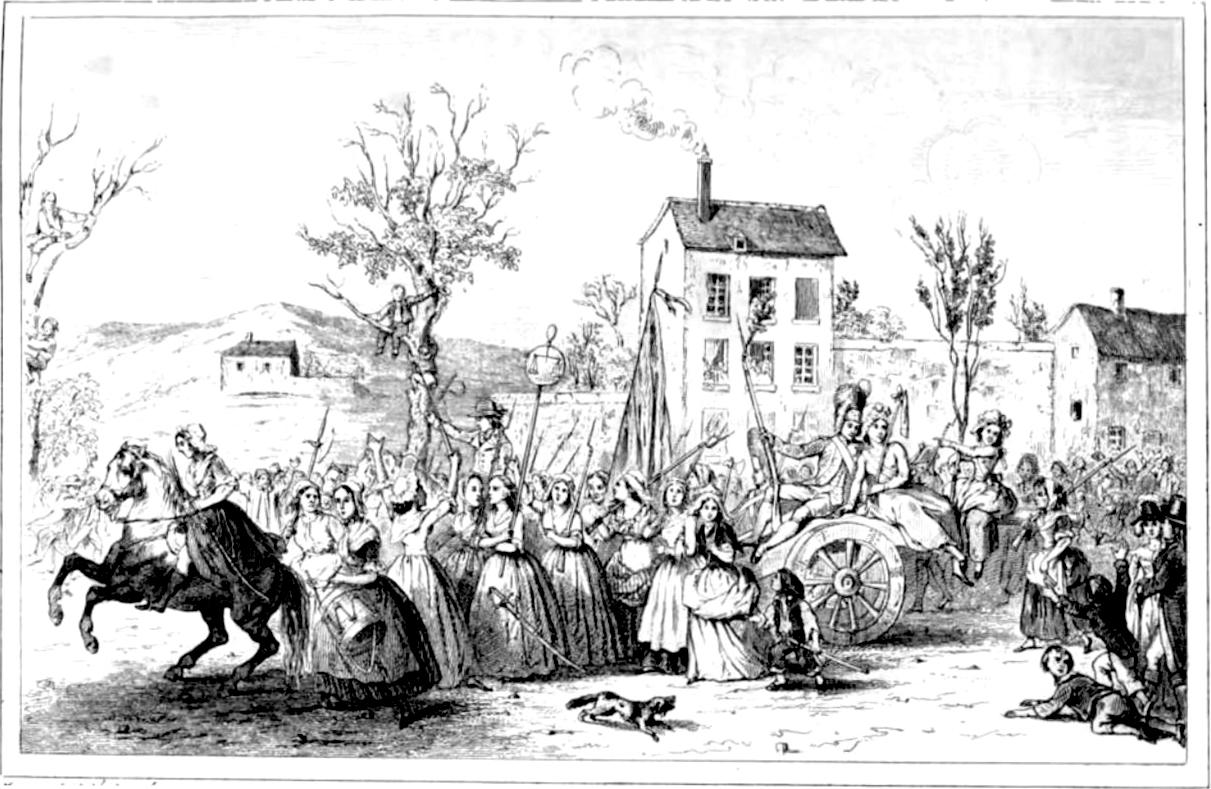

Although the price of bread was not the root cause of the French Revolution, increasing bread prices contributed to a sense of social and economic inequality between the rich and the poor. With half of a day’s wages spent on bread, bread was the staple of the working class diet. Most of the French population lived in agriculture during the 1780s and worked on larger farms to overcome the daily problem of hunger, a problem that intensified during the years of poor harvest. When crops failed in 1788 and 1789, the price of bread sopped up most of a day’s wages. An additional tax on salt only inflamed the peasants’ anger towards the monarchy. Farmers were forbidden to sell wheat at the market and bakers were supplied with a specific quantity of flour and regulated about the kind of bread they baked. Hungry peasants migrated to the cities looking for work. Hungry, poor, and angry—the perfect foment for a revolution.

“Bread riots” frequently followed increases in the prices bread and as mistrust ran deep, bakers frequently became the scourge of the public’s wrath. Because price increases for bread have sown the seeds for social revolution, legal mandates forced bakers to sell their loaves at a ‘just and moral price”, regardless of the market price of wheat.

Over time, bread was repurposed as a public service that prevented citizens from rioting. Police enforced its pricing and armies were responsible for its distribution. Baking bread was no longer a trade but a civic duty. Recipes were not created according to the baker’s whim, but tailored to meet the economic needs of the community. From 1266 to 1863, the English Assize of Bread defined bread as:

“Wastel bread was the standard superior loaf, which varied in weight depending on the price of corn. It was white and eaten by the rich. Cocket bread was like wastel, but made of slightly inferior flour. Simnel bread was a rich cakey thing, also eaten by the wealthy. Bread of whole wheat (panis integer) was the bread eaten by the masses, unless they were really poor, in which case they might eat treet or “household bread” made of coarse brown unbolted meal; poorer still,. “bread of common wheat” or “horse bread”, a loaf made from the miller’s refuse…” (Swindled, Bee Wilson, p. 68-69)

The rich and the poor alike could be assured of the quality and identity of the bread they paid for. This was important during an era where unscrupulous millers and bakers would adulterate the flour with aluminum, chalk, or sawdust to bulk up the flour or make it look whiter. Bakers indented loaves with their seal and were not allowed to sell loaves through a middleman. Rising bread prices are still keenly felt by the poor and many revolutions continue to be borne and fought in the name of unjustly priced bread.

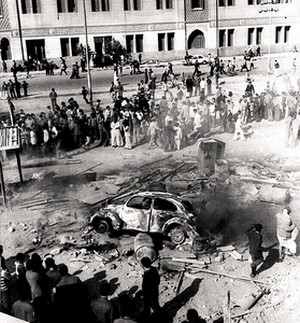

In the United States, any merchant or government perceived as neglecting the bread supply faced violence and bread riots as was the case during the Boston Bread Riots of 1710 and Richmond (Virginia) Bread Riots of 1863. Most recently, the toppling of Egypt’s Islamist government was sparked by its inability to stem the tide of Egypt’s low standard of living. Once the military took over, its main focus was to restore order by maintaining the country’s supplies of wheat. Because its own farms couldn’t meet demand, the government imported wheat making Egypt the world’s leading importer of wheat. It’s a delicate dance between the power of the bread keepers and the will of the bread eaters.

While subsidized bread is still a fixture of life in developing countries, the quandary with bread prices in a global marketplace is that they are affected by the cost of wheat flour—and not necessarily by the price of the wheat berry itself. From month to month, the price of wheat flour fluctuates and the variables go beyond supply and demand: foreign and domestic agricultural policies, economic climate, strength of the US dollar, crop surpluses or shortfalls, crop conditions, global wheat prices. The price of wheat flour varies by region as most countries cannot grow enough wheat to support the native population. Overall, prices have been trending upwards because of bad harvests from 5 years ago that are straining to support increased populations. Even the crisis in Crimea will impact the price of our daily loaf as the Ukraine is the sixth largest wheat supplier in the world, most of which is exported to the Middle East and North Africa.

As government intervened to protect the identity of bread and during the 18th century when French police enforced exactly how loaves were to be made, people knew what bread was—a preparation of water, flour, salt and leaven (usually sourdough or yeast). If the quality slipped because of poor grain, improper weights, or nonpermitted ingredients, people knew enough to complain. Everyone knew what good bread was and the government made sure they got it. The baker would be stripped of his membership within the trade guild, fined, imprisoned or worst of all, not permitted to bake professionally. In today’s marketplace, who do you complain to if you are sold a bad loaf? An anonymous customer service rep who will mail you a refund check for your pittance? One thing is certain; you will never meet the person who made your loaf because there is no person. Like many other aspects of life, we’ve relegated the tasks of growing, preparing, and cooking our food to industrial machines. Although periodic wheat shortages put economic pressures on bakers, the erosion of bread standards is ultimately due to the bread eaters who don’t demand properly made bread.

Leave a comment